I was astounded at what happened when I tested my theory with this student. Subsequent experiences convinced me that sometimes, all that students need so they can judge these crossings is a good intuitive understanding of their crossing time.

Click here if you want to see a video of this crossing

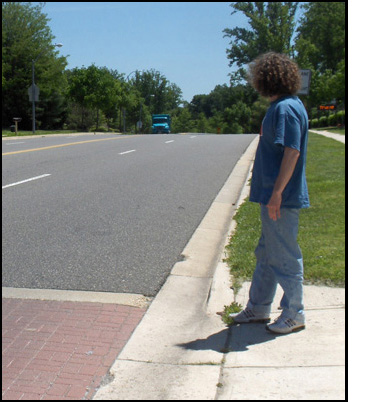

The student (represented in these photos by my son, Stephan) was 14 years old, and had highly functional vision.

I wanted to teach him to be able to recognize Situations of Uncertainty for gap judgment (that is, situations where he doesn't have enough warning of the approaching vehicles

to know whether or not it is clear to cross).

I chose the crosswalk in front of his school, where the street is 4 lanes wide, and there is no traffic signal or stop sign [see photo to the left].

I asked his mother to join us for the last part of the lesson.

The student (represented in these photos by my son, Stephan) was 14 years old, and had highly functional vision.

I wanted to teach him to be able to recognize Situations of Uncertainty for gap judgment (that is, situations where he doesn't have enough warning of the approaching vehicles

to know whether or not it is clear to cross).

I chose the crosswalk in front of his school, where the street is 4 lanes wide, and there is no traffic signal or stop sign [see photo to the left].

I asked his mother to join us for the last part of the lesson.

I didn't feel comfortable timing the student's crossing there, because I couldn't hear or see the cars from the right far enough to know whether it was clear to cross (if you watch the video, you know what I mean!). So before I started the lesson, I measured the width of the street by counting paces across the crosswalk [photo to the right] and then measured an equal distance from a curb in a nearby parking lot. Luckily, it ended at a white line near a hedge that I used as a marker [below].

I started the lesson by taking the student to the crosswalk, and telling him that there are situations where it is not possible for people to see or hear the traffic with enough warning to know whether or not something is coming that would have to slow down to avoid hitting them.

I made sure he understood that this is true of everyone, and not because of any deficiency on his part.

I started the lesson by taking the student to the crosswalk, and telling him that there are situations where it is not possible for people to see or hear the traffic with enough warning to know whether or not something is coming that would have to slow down to avoid hitting them.

I made sure he understood that this is true of everyone, and not because of any deficiency on his part.

I said I wondered if he would be able to recognize such a situation (this kind of challenge -- being able to recognize Situations of Uncertainty -- seems to work better than talking about whether a crossing would be "safe," especially for teenage boys who show no fear of anything!).

I asked him to watch what happens with the traffic here, and tell me if he thinks it is one of those situations where it isn't possible to see far enough to know whether or not something is coming that could reach him during his crossing, and told him we would then test his judgment. After he watched for a few moments, we saw a vehicle from the right appear just over the top of the hill.

I said, "Oh, there is a good example! If you had started to cross just before you saw that truck -- that is, when you didn't see anything coming -- would the driver have had to slow down to avoid hitting you? Or would you have made it to the other side before he got there?"

I said, "Oh, there is a good example! If you had started to cross just before you saw that truck -- that is, when you didn't see anything coming -- would the driver have had to slow down to avoid hitting you? Or would you have made it to the other side before he got there?"The truck flew past us very soon after we saw it. He calmly said he could have made it across all four lanes before the truck got there, without the driver having to slow down.

I thought to myself "In what UNIVERSE could you possibly be able to cross before it gets here?!" but all I said was "Great, thanks! Okay, now we are going to test your judgment and see if you were right.

To do that, we first need to find out how much time you need to cross the street. I have marked an area in the parking lot that is the same width as this street, so let's go there and time your crossing."

I thought to myself "In what UNIVERSE could you possibly be able to cross before it gets here?!" but all I said was "Great, thanks! Okay, now we are going to test your judgment and see if you were right.

To do that, we first need to find out how much time you need to cross the street. I have marked an area in the parking lot that is the same width as this street, so let's go there and time your crossing."

In the parking lot, he walked quickly from my marker to the curb while I timed him. I told him it took 10 seconds. He crossed back and, again, it took him 10 seconds.

When thinking about how badly he misjudged the vehicle at the crosswalk, I decided to do a little experiment.

We stood at the marker and I asked him to pretend he was crossing to the curb, and tell me when he starts (in his mind), then tell me when he thinks he finishes the crossing.

When thinking about how badly he misjudged the vehicle at the crosswalk, I decided to do a little experiment.

We stood at the marker and I asked him to pretend he was crossing to the curb, and tell me when he starts (in his mind), then tell me when he thinks he finishes the crossing.

He said he was starting his imaginary crossing, and I started the stopwatch. Five seconds later he said he would have reached the other side. I thought to myself, "AHA! THAT explains a LOT!"

I told him that was only half the time he needed. I said, "I'll show you what your crossing is like. If you started NOW," [I started the timer] "you'd be crossing ..... you'd be in the middle about now, and ... [the stopwatch said 10 seconds] NOW you would be on the other side. Okay, you try again with another imaginary crossing."

He said he was starting to cross (in his mind), and I started the stopwatch again. This time he didn't say he was finished until exactly 10 seconds had passed. I knew he understood it when he timed it correctly a few more times. It was not until later that I appreciated how quickly he learned it -- most of my clients have needed more practice timing imaginary crossings than he did before they "get it."

So then we went back to the crosswalk again and I said, "Now that we have your crossing time, we can test whether you were right about being able to see far enough to know whether something is coming that might have to slow down to avoid hitting you. Please watch the traffic from the right and tell me as soon as you see something that might be a vehicle coming."

He watched the traffic, and then said he saw a car coming. I started the timer, and then stopped the timer when the vehicle passed in front of us.

He watched the traffic, and then said he saw a car coming. I started the timer, and then stopped the timer when the vehicle passed in front of us.

"What do you think?" I said. "If you had started your crossing just before you saw him, would you have made it to the other side?"

"No way!" he said.

I told him he was right -- it passed us less than 7 seconds after we saw it.

I asked where he'd be when it passed, if he had started crossing just before he saw the car (when he still thought nothing was coming). He said correctly that he would have been in the third lane, right where the car passed. It definitely would have had to slow down or take evasive action to avoid hitting him.

By this time, his mother had joined us. The student and I talked about whether it was likely that a car would be coming just as he started to cross, and how likely that it would stop for him. He thought it was fairly likely that a car would be coming (it was fairly busy at that time) but that it was also likely that the driver would slow down or stop for him because it was a crosswalk in front of a school, with a pedestrian sign facing the drivers from each direction. I asked if he thought the risk of crossing there was acceptable (that is, whether he felt it was "safe" to cross). He said it was.

To my surprise his mother, who works as a school security officer, agreed.

Whenever my students and I find ourselves in a situation where it's not possible for them to know whether it's clear to cross, regardless of whether the risk is acceptable, I always talk about alternatives. So I said, "Okay. There will be times in your life that you will find situations where you don't think the risk is acceptable, so let's talk about what you might do then. Let's pretend, for example, that you wanted to cross the street to catch a bus, and you felt that the risk of crossing here was not acceptable. What else could you do?"

He came up with some ways he could reduce the risk of crossing there as well as some good alternatives, and then said, "Another alternative is that I could cross to the middle and then wait and cross the second half."

I said, "That alternative has some risks too -- there is no place to stand, it's just a few painted lines, so you would be standing in the middle of the street, and if you continue crossing because a car slows down or stops for you, another car might speed past it without seeing you. Are you okay with that?"

He said yes.

I turned to his mother and asked, "Would you be okay with that?"

"No," she said with her eyes wide with alarm, "I'm NOT okay with that! It is not safe to stand there in the middle of the street."

I told them about the alternative of starting to cross when it seems clear but turning around if something comes before you reach the middle. I explained that this works only when you have enough warning to know it's clear to cross at least half the street, and we all agreed that this situation met that criteria. They both felt okay with that alternative. I also explained the kinds of engineering changes that can be made to narrow the crossing and make it safer (these can be seen at Environmental Modifications). We continued talking about other alternatives, and then finished the lesson.

In this lesson, the student had greatly improved his ability to judge whether he has enough warning about the approaching vehicles to be sure there is time to cross. The lesson also gave him some experience evaluating the risks and making decisions (which at his age are ultimately made by his parents but he needs to prepare for adulthood) as well as considering alternatives. And of course I had learned a lesson too, about the importance of having an intuitive understanding of crossing time!

So there I was, standing with my client facing a street she'd have to cross to get to her community swimming pool.

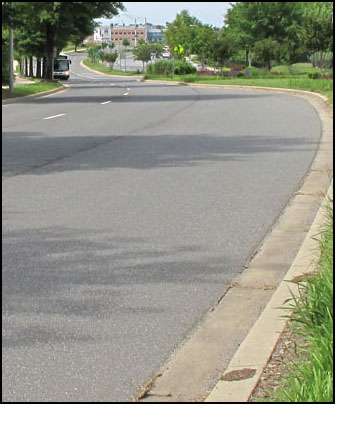

The street looked like the one in the photo to the right -- it had two narrow lanes on each side of a wide, grassy divider, and to our right there was nothing except the entrance into her apartment complex.

So there I was, standing with my client facing a street she'd have to cross to get to her community swimming pool.

The street looked like the one in the photo to the right -- it had two narrow lanes on each side of a wide, grassy divider, and to our right there was nothing except the entrance into her apartment complex.

Mimi was learning about

Mimi was learning about

Then we walked to the corner of his community entrance on a busy two-lane street called Donaldson Road (shown to the right) to observe the traffic and talk about crossings.

He said he'd be safe crossing the entrance as long as he was in the crosswalk.

Then we walked to the corner of his community entrance on a busy two-lane street called Donaldson Road (shown to the right) to observe the traffic and talk about crossings.

He said he'd be safe crossing the entrance as long as he was in the crosswalk.

In two of those situations (the first two photos to the left), the road was straight and you could hear the cars at a distance even when you tried to block the sounds with a board.

In another situation (the last photo), no matter how quiet it was, you couldn't hear the cars until they came around a sharp bend in the road.

In two of those situations (the first two photos to the left), the road was straight and you could hear the cars at a distance even when you tried to block the sounds with a board.

In another situation (the last photo), no matter how quiet it was, you couldn't hear the cars until they came around a sharp bend in the road.

However in at least one situation (when traffic was coming over a hill, as shown in the photo to the left), that same increase in ambient sound dramatically reduced the ability to hear the cars.

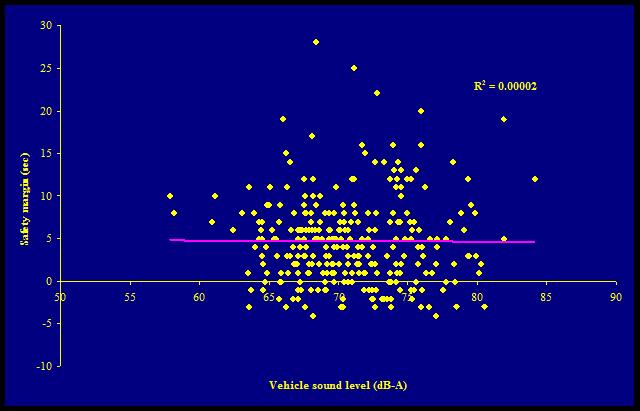

Click here if you want to see the graph showing how the level of ambient sound at each of the 6 situations affected the ability to

hear the vehicles, as measured by the average "safety margin" -- notice how the line of the safety margin is dramatically reduced for the "hill" situation between 38 and 40 db(A) (it is also reduced for the "trees" situation but that varies wildly and randomly as the background noise increases).

However in at least one situation (when traffic was coming over a hill, as shown in the photo to the left), that same increase in ambient sound dramatically reduced the ability to hear the cars.

Click here if you want to see the graph showing how the level of ambient sound at each of the 6 situations affected the ability to

hear the vehicles, as measured by the average "safety margin" -- notice how the line of the safety margin is dramatically reduced for the "hill" situation between 38 and 40 db(A) (it is also reduced for the "trees" situation but that varies wildly and randomly as the background noise increases).

Freaky problem

Freaky problem Real-life situation:

Real-life situation:

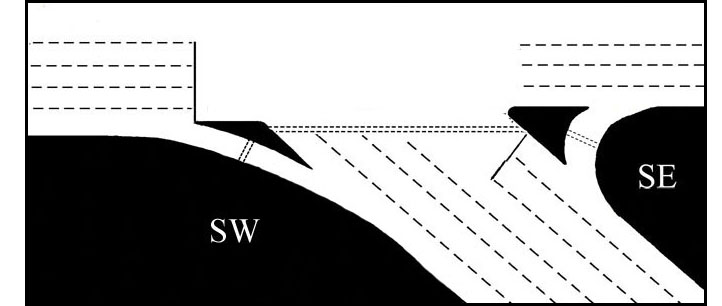

The photo to the left shows the street we were facing, and the series of photos below illustrate how the vehicles move as they approach us.

The first photo below shows a bus and a car passing through the area where we could hear all the vehicles.

The car remains visible throughout the approach, but the bus disappears behind the trees and then appears again.

The photo to the left shows the street we were facing, and the series of photos below illustrate how the vehicles move as they approach us.

The first photo below shows a bus and a car passing through the area where we could hear all the vehicles.

The car remains visible throughout the approach, but the bus disappears behind the trees and then appears again.

In our study of the ability of blind people to hear approaching vehicles at uncontrolled crossings, Dr. Rob Wall Emerson and I recorded the detection of 805 vehicles among 6 different road features, such as straight, curved, hills, etc. (

In our study of the ability of blind people to hear approaching vehicles at uncontrolled crossings, Dr. Rob Wall Emerson and I recorded the detection of 805 vehicles among 6 different road features, such as straight, curved, hills, etc. (