CHANNELIZED RIGHT-TURNING LANES

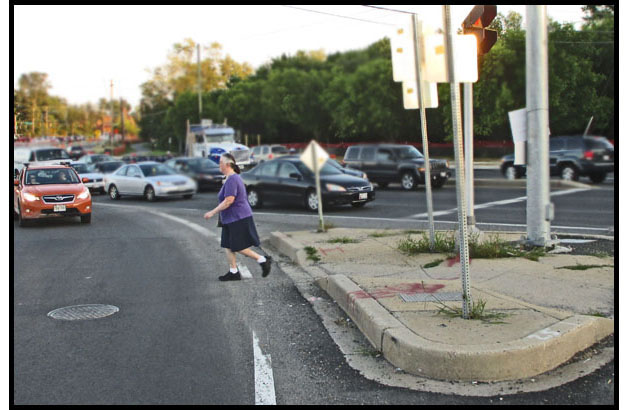

- Channelized right-turning lanes are separated from the rest of the intersection by painted lines or raised barriers, usually in the shape of a triangular island, such as the one shown in the photos above (the first photo was taken many years ago, when the lines of the crosswalk were still visible).

Traffic in these channelized right-turning lanes comes from one street (the "upstream" street), turns right and then has to yield to or merge into traffic on the perpendicular street (the "downstream" street). There is usually a pedestrian crosswalk where drivers are supposed to yield to pedestrians, although drivers do not always reliably stop (see experiments at channelized right-turning lanes in Maryland and California).

- The island may have an acceleration or a deceleration lane or both;

- The radius of the turn can vary;

- There may be a signal specifically for traffic in the channelized right-turning lane.

Acceleration and deceleration lanes:

Acceleration and deceleration lanes:

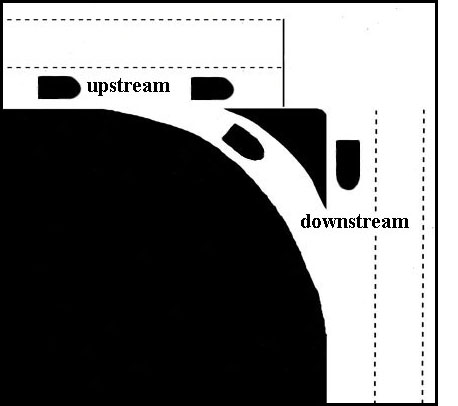

In the drawing to the left, there is no acceleration or deceleration lane. As a result, traffic approaching the intersection in the lane nearest to the curb can go straight or turn right when it reaches the right-turn lane. Traffic coming out of the right-turn lane must yield to traffic before entering the other street.

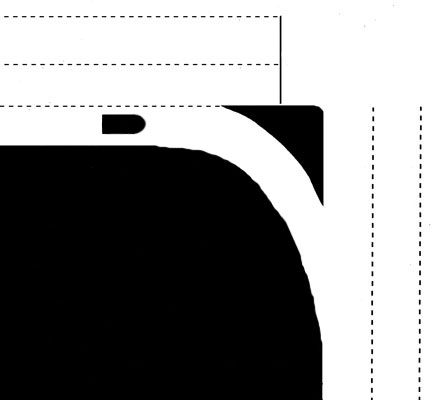

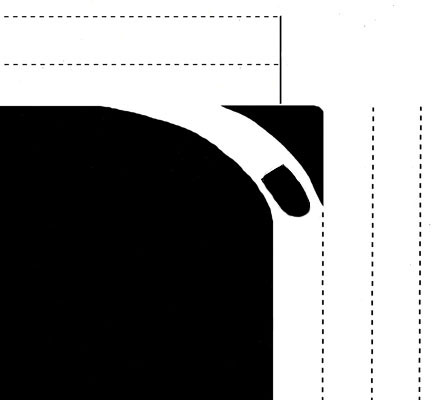

The drawings below have acceleration and/or deceleration lanes:

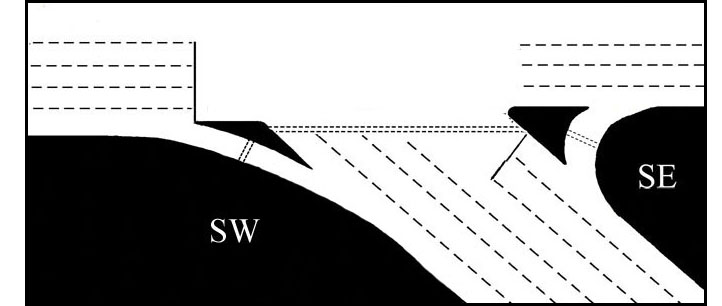

Radius of the turning lane:

-

The radius of the turning lane can be small (SE corner in the drawing to the left) or large (SW corner).

Drivers turning right in a lane with a small radius will need to slow down more than they do to turn in a lane with a large radius.

- Some channelized right-turning lanes have a signal, directing traffic in those lanes to stop.

Because of variations such as turning radius and/or the presence of acceleration and deceleration lanes and signals, channelized right-turning lanes present a wide range of difficulty for pedestrians to cross.

For example, those which have a deceleration lane, a wide radius, and an acceleration lane with no traffic signal are the most difficult to cross, because the deceleration lane, combined with the wide radius, means that the traffic does not have to slow down to approach the intersection, and it does not even have to slow down to yield to perpendicular traffic if there is an acceleration lane. The SW corner of the drawing above has each of these features except the acceleration lane -- click here for an analysis of the risks of crossing there.

On the other hand, channelized right-tuning lanes which have a tight radius and no acceleration or deceleration lanes are much easier to cross. The presence of an accessible pedestrian-actuated signal to direct the traffic to stop for pedestrians can also make it easier.

The crosswalk is usually located halfway between the beginning and the end of the separate lane (midway between the corners of the island) and aligned perpendicular to the curbs, as shown in the photos at the top of this page and the drawing above.

The crosswalk is usually located halfway between the beginning and the end of the separate lane (midway between the corners of the island) and aligned perpendicular to the curbs, as shown in the photos at the top of this page and the drawing above.

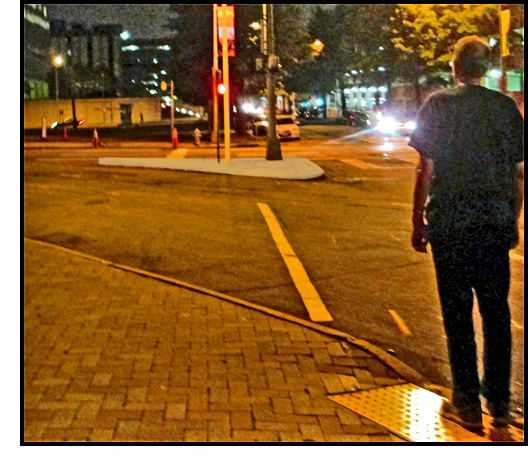

However sometimes it is located at the end of the right-turning lane, where traffic has to yield to vehicles on the downstream street, such as the crosswalk to the island in the photo to the right. When this is the case, the traffic often is going more slowly and is therefore more likely to stop than it is in the middle of the lane, but drivers may not see pedestrians to their right because they are looking only to their left for vehicles. Also, alignment can be challenging because at that point, the curb is almost parallel to the "downstream street" (the street parallel to the crossing). In the photo to the right, the pedestrian is standing on the curb ramp which is aligned to go almost directly into the parallel (downstream) street, rather than toward the island.

Strategies for crossing:

- Click here for ideas for crossing roundabouts and channelized right-turning lanes generated by participants at a workshop.

- Cross when there is a gap in traffic that is long enough (this can be done only when there is enough warning of approaching vehicles to be able to know when it is clear to cross -- see "Situations of Uncertainty for Gap Judgment").

- Get drivers to yield (see Bourquin et al, 2018). If crossing more than one lane, there should be assurance that traffic in all lanes has yielded.

-

Blind people may not always reliably detect the presence of yielding cars (Inman, Davis, & Sauerburger, 2005) so the ability to detect yielding vehicles may need to be enhanced, perhaps with a strategy to get drivers to honk or announce their presence, or with an expertly-used Electronic Travel Aid.

- bending forward and cupping your ear, as if trying to listen harder, or

- holding up a sign saying something like "HONK if you have stopped."

Strategies that have been successful for getting drivers to honk or roll down their window to say they are waiting include

Bourquin,Eugene A.; Wall Emerson, Robert; Sauerburger, Donaand Barlow, Janet M. (2018). Conditions that Influence Drivers' Behaviors at Roundabouts: Increasing Yielding for Pedestrians Who Are Visually Impaired Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, January-February 2018; Volume 112, Number 1, pp. 61-71.

Inman, Vaughan. W., Davis, Gregory. W., and Sauerburger, Dona. (2005) Pedestrian Access to Roundabouts: Assessment of Motorist Yielding to Visually Impaired Pedestrians and Potential Treatments to Improve Access. Federal Highway Administration Report DTFH61–02–C–00064

Return to Ideas for Crossing Roundabouts and Channelized Right-Turning Lanes

Return to Signals

Return to home page