- Please review this section carefully -- it contains the basic ideas and terminology that are necessary to understand the rest of this self-study guide.

We hope we dispel some common misconceptions here, and give you the real scoop on how signals work,

so it's important to get these terms and concepts down before you move on to complexities you need to master!

- Before we explain some of the basic concepts, we should explain a few terms we'll be using throughout the Self-Study Guide:

- Conflict (traffic pattern): when the signal is programmed such that two road users (vehicle-vehicle or vehicle-pedestrian) can share the same space at the same time while obeying the traffic signals, allowing for possible collisions. The law always designates which user has the right-of-way in that situation.

- Conflict (incident): when two road users (vehicles / pedestrians) are on a collision course that will result in a crash unless one of them takes evasive action such as slowing down or stopping for the other.

MAJOR and MINOR STREETS

-

Many intersections have one street that is busier than the other street - the busier street is often wider.

We will refer to the busier/wider street as the major street and the other street is the minor street.

At T-intersections, where one street ends while the other street goes straight through the intersection, we refer to the straight-through street as the "major" street.

-

We will be referring to the pedestrians' parallel street, which is the street beside them (with traffic going parallel to their line of travel and crosswalk).

The perpendicular street, of course, is the street they are facing and intending to cross.

- When we say "crossing clockwise" we mean crossing around the intersection clockwise, with the parallel street on the right.

Of course "crossing counter-clockwise" is the opposite (the parallel street is on the left).

- When we mention "conflicts" in the movement of vehicles and pedestrians, we are referring either to the design of traffic patterns, or to incidents that occur in the intersection.

Definitions of these are:

- You have a question about a signal, or something isn't working, who ya gonna call? The traffic engineer, of course!

- reporting a malfunctioning signal;

- requesting special features for a pedestrian pushbutton;

- increasing the minimum time for a pedestrian or traffic signal.

- Determine which jurisdiction is responsible for that intersection (Don't sweat this -- if you contact the wrong one, they'll probably be able to tell you who to contact).

- Is it state/province? In the U.S., if the intersection is along a street that is numbered (such as "Route 66"), the state is probably responsible for it.

- Is it local? In the U.S., anything that is not on a state highway is usually the responsibility of the local jurisdictions, such as county or city. However, states sometimes are responsible for intersections along local roads and vice versa.

- Find the right agency: In the U.S., the traffic engineers who are responsible for signals are usually housed within the department of transportation or public works, often in a separate division for traffic signals. If you can't find the appropriate agency or office, call for government information and explain that you want to contact those who are responsible for the traffic signal in question.

Traffic engineers are usually very willing to answer your questions and even meet you at the site to look at concerns. We've found that the experience is often a positive one for both of you, especially if you are knowledgeable about how signals work, can talk their language, and are willing to understand the parameters they have to deal with. Having a good working relationship with the traffic engineers in your area can be extremely helpful -- both of you will learn and benefit from it and can become valuable resources for each other.

Your students should also become comfortable with the idea of contacting the engineer for a variety of issues, some of which are explained in this Self-Study Guide, such as

- Now we're ready to explain some of the concepts that may be helpful for understanding the rest of the Self-Study Guide:

- each part (for example, just the green) is an interval;

- the green and yellow intervals together make up a "vehicle phase" -- the phase when vehicles can be in the intersection.

- DON'T WALK interval means the pedestrian should not be in the crosswalk. That's pretty straight forward, isn't it?

- WALK interval means, basically, it's time to begin to cross. It is not the "time you have to walk across the street"!

The standard WALK signal is only 6 seconds long (sometimes shorter!) which is barely enough time for most of us to get across just two lanes.

When blind pedestrians understand that they are promised enough time to cross the entire street if they step off the curb during the WALK signal, they can focus on what they need to do. More importantly, if you begin the crossing after the WALK signal has finished, you are not guaranteed that "clearance" time!!! You may very well run out of time while you're in the crosswalk. - FLASHING DON'T WALK interval ("Pedestrian Clearance Interval") means the pedestrian should finish her crossing. It does NOT mean the pedestrian is running out of time, or that she needs to rush or run!

This is important because pedestrians who are blind have many tasks to attend to while crossing, such as maintaining alignment, monitoring for turning vehicles, and attending to input from their cane.

Rushing because you think you are out of time is not helpful!

The secret is that the Flashing DON'T WALK interval is programmed to provide enough time to cross even for average walkers, so you should be able to proceed and complete the crossing in a calm, efficient manner.

ACTUATION

- First, be aware that modern traffic and pedestrian signals are more complex than most people think . . .

so complex that more than 90% of the intersections with signals in the United States have a computer right there, controlling how and when vehicles and people move, based on what vehicles or pedestrians are detected at the intersection!

The term for this is actuation. The fact that the computer for actuated signals determines the order and length of the signals by detecting vehicles and pedestrians means that these signals are unpredictable. They may change throughout the day, and even change from moment to moment. This is explained in our section Traffic Signal Actuation.

-

Every intersection has what engineers call a signal cycle, which is determined by the signal timing plan designed by the traffic engineers for that intersection.

Signal cycle

- The signal cycle includes one entire loop through the sequence of signals.

For example, in a typical cycle, a driver would see a red light (we'll be calling these signals, not lights), then a green signal, then a yellow signal.

And then it starts again with another cycle.

Exactly how the cycle is presented has a lot to do with the signal timing plan programmed into the computer.

In the cycle there are sections of time or movement, called intervals and phases. Think about that green, yellow, and red signal sequence for vehicles -

- The signal timing plan determines the signal cycle for that intersection as well as the timing of its phases and intervals.

Of course the timing of signals at actuated intersections will vary, depending on whether and how many vehicles and pedestrians are detected, but even those signals have certain time parameters programmed into the computer.

For example, the signal timing plan at many actuated intersections gives the major street a minimum amount of time for its signal to stay green. That means that when vehicles or pedestrians are detected wanting to cross the major street, they may have to wait until the minimum time that was set for the major street's green signal has passed.

Conversely, there is often a maximum amount of time that an actuated signal will stay green for the minor street. If there are more vehicles detected on the minor street once that time has passed, they'll get a red signal and have to wait until the major street has had its turn again, and then they'll get another green signal.

In a later section you will learn that at some signals, for example at actuated signals with no pedestrian pushbutton, the engineers sometimes also set a minimum time for the signal of minor streets to be long enough to allow pedestrians to cross the major street, and a maximum time for the signal of major streets.

What will pedestrians see when they look at the signal on the other end of the crosswalk? We all know this, right? There may be words or symbols, but they would typically see a DON'T WALK (or orange hand symbol), then a WALK (or white man walking symbol), then a FLASHING DON'T WALK (or flashing orange hand symbol).

-

For reasons explained in our section Signalized Traffic Patterns for Vehicles, we recommend that for situations where the pedestrian does not have access to the pedestrian signal, the best cue for beginning to cross is usually the surge of the near-lane-parallel traffic.

So it is critically important that you understand what on earth near-lane-parallel traffic is!

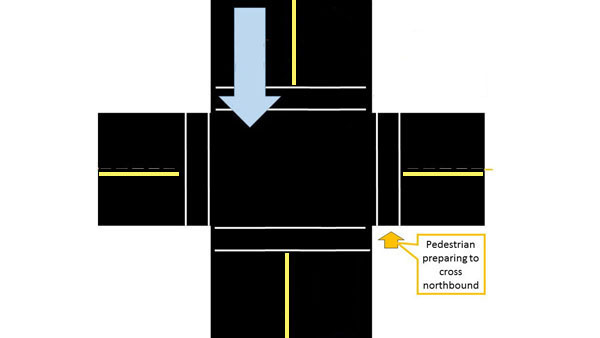

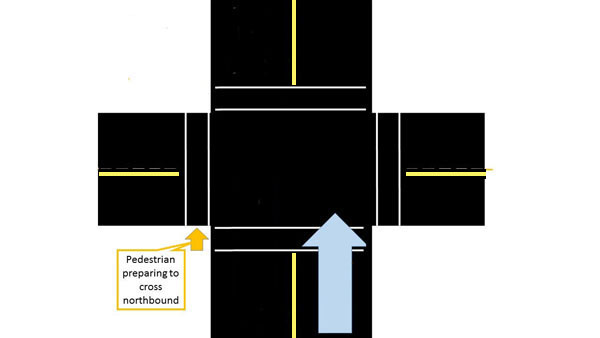

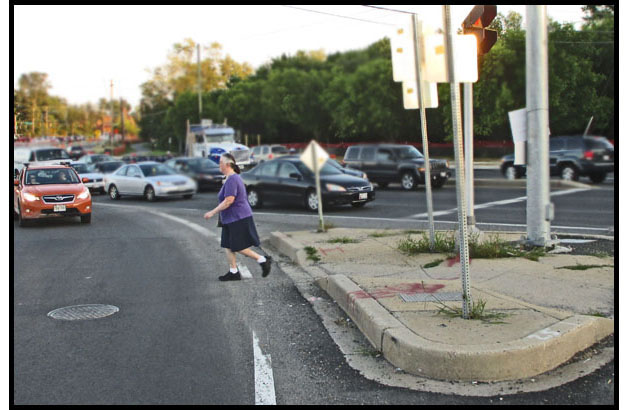

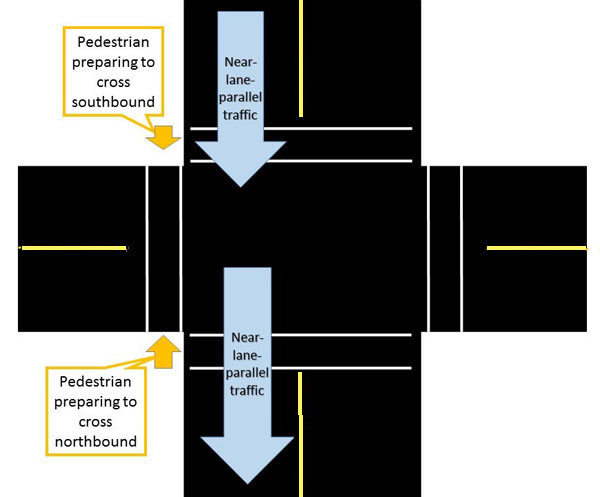

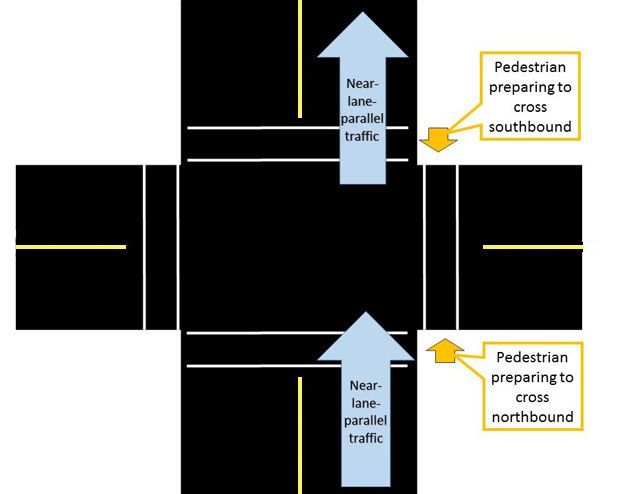

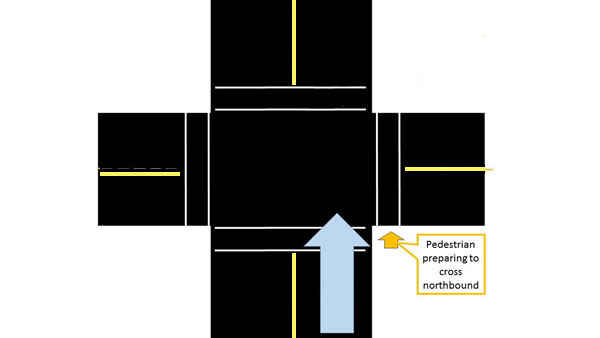

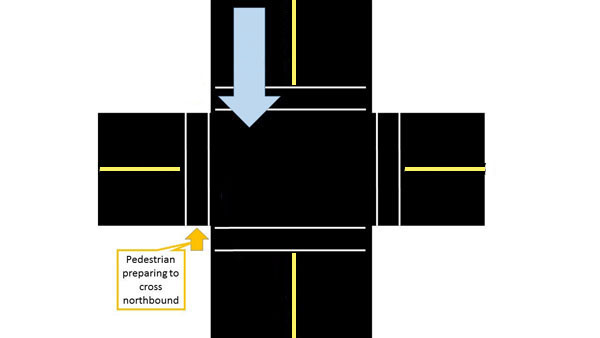

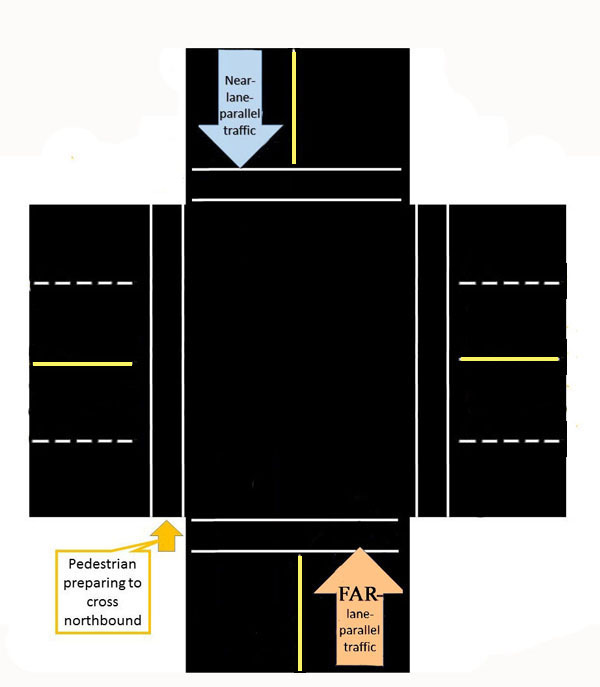

Basically, near-lane-parallel traffic is the traffic in the parallel street that is traveling straight through the intersection in the lanes closest to the crosswalk that you are using to cross the street, as shown in the illustrations below. Sounds simple! But this can be a little tricky, because sometimes the parallel vehicles that are physically nearest to the traveler are not in the lanes nearest to the traveler.

When teaching this to students, as illustrated in the video to the right, we can point out that the correct traffic lanes are the lanes closest to the crosswalk being used to cross. There may be traffic in those lanes that is turning right or left, but the cue to focus on is the straight-through traffic. That traffic may be going the same direction as you are, or may be coming toward you from the opposite direction. There may be more than one lane of traffic making that movement and there also may be a right-turn lane between you and that traffic.

We've illustrated where the near-lane-parallel traffic is in the drawings below.

Left: For pedestrians crossing in the West crosswalk (that is, from NW to SW corner and vice versa), near-lane parallel vehicles are those that are traveling south on the west side of the street.

Right: For pedestrians crossing in the East crosswalk (that is, from NE to SE corner and vice versa), near-lane parallel vehicles are those that are traveling north on the east side of the street.

When the parallel street is on your left (as it is in the illustration here), the surge of that near-lane-parallel traffic will be very close to you on your left (and slightly behind you).

When the parallel street is on your right (as it is in the illustration here), the surge of that near-lane-parallel traffic is actually in front of you (and slightly to your right) on the other side of your perpendicular street.

What Near-Lane Parallel traffic is NOT

Remember, we are talking about the traffic in the nearest LANES of the parallel street, not the nearest TRAFFIC.

This can be very confusing when the parallel street is on your right and the perpendicular street is wide, as shown to the left. In this situation, the near-lane-parallel traffic is actually waiting further from you than traffic that is in the lanes of the far side of the parallel street!