Polarization is destroying democracy,

and we can DO something about it!

by Dona Sauerburger

Written in 2020, with notes added in 2022

Polarization - an "us vs. them" mentality and being unwilling to listen to and understand others or even compromise to meet common goals -- has made our government more and more dysfunctional, and divided our citizens.

On a national level, this polarization can destroy our democracy, which requires compromise to function (Diamond, 2019). For example, Chili enjoyed a long history of peace and democracy, and in 1967 was considered the most politically stable country in Latin America. Its citizens could not conceive of having to live under a dictatorship, just as we cannot conceive of it here in the U.S. now. However, in 1973 the government was overthrown and a dictatorship established, leading to years of brutal suppression, torture, thousands of people being killed, and about 100,000 Chileans fleeing into exile.

They never saw it coming, but according to Diamond (2019), the government was overthrown because of "Chili's increasing polarization, violence, and breakdown of political compromise, culminating ...in the arming of the Chilean far left and ... warnings of impending massacres by the far right" (page 158). Chili was not the only country to be affected by polarization -- "both Chili's and Indonesia's internal crises arose from political polarization, disagreement about deeply held core values, and a willingness to kill and to risk being killed rather than to compromise" (Diamond, page 174).

But there is hope if we work to end this polarization -- Chili managed to become the most democratic and richest country in Latin America by ending the "intransient rejection of political compromise" (Diamond, page 172).

On a personal level, polarization can drive us apart, even convincing us that certain groups of people are "others" who pose a danger to us, or deserve our contempt and repression. We all know people who avoid speaking with friends, colleagues and even family members because of the way that they voted, and the percentage of parents who prefer that their children not have an interpolitical marriage (55%) is greater than the percentage of people who don't approve of interracial marriages (13%) (Enochs, 2017).

This "othering" of people has even led to violence. Americans who considered people who are Jewish, or homosexual, or African-American, or Hispanic as "others" who need to be repressed or exterminated have gone into a synagogue, a gay night club, an historically Black church, and El Paso to terrorize or eliminate them. I've personally seen what can happen when anger turns to violence. In March, 2018, an angry tenant ran over our son to make him "learn some respect," and he may never fully recover. A few months later, an angry demonstrator in Charlotte intentionally ran his vehicle into a crowd and killed a protester. I was pleased when our President pointed out that there were good people on both sides -- recognizing the good in people, and refusing to consider anyone as "others" who are inherently evil, is an important step towards unity and depolarization. It is unfortunate that a few days later, he retweeted a cartoon showing the Trump train running over a CNN reporter.

What can we do about it?

To stop the polarization that is destroying our country and our traditional American culture, we can stop perpetuating it ourselves, and join the growing number of people who are turning away from the division and hate and the "outrage industrial complex" that profits from it.

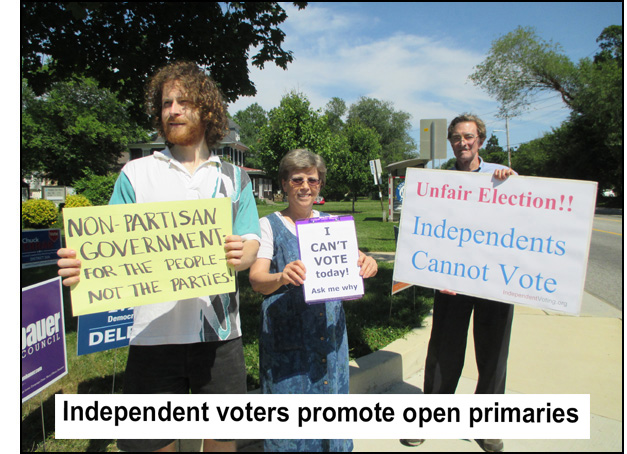

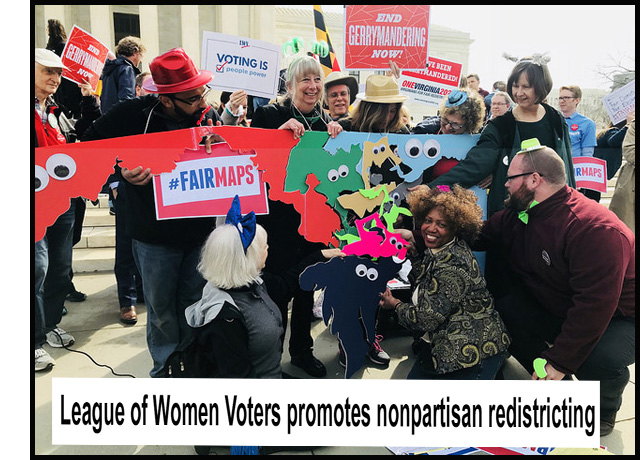

On a political level, we can promote nonpartisan election systems, such as supporting transparent redistricting that doesn't marginalize political opponents with gerrymandering, and supporting open primaries, which studies indicate increase candidates' bipartisanship (Alvarez and Sinclair, 2012, Grose, 2016).

On a political level, we can promote nonpartisan election systems, such as supporting transparent redistricting that doesn't marginalize political opponents with gerrymandering, and supporting open primaries, which studies indicate increase candidates' bipartisanship (Alvarez and Sinclair, 2012, Grose, 2016).

And we can avoid becoming involved in the power games of political parties, and instead insist that legislators work together. When a delegation from the League of Women Voters of Maryland visited Congressional offices in 2019 and asked legislators to work with their colleagues across the aisle to help get some bills passed, we were told that the way to make that happen is to help elect more members of their party into office. Rather than agree to work with their colleagues and build consensus on shared values, these legislators seemed to prefer for us to help strengthen their party in order to get the things we want. We can let them know that we find this unacceptable, and that we want them to work on our behalf by compromising to get things done. [Braver Angels now has a program, Braver Politics, to help elected officials work together in a non-partisan way.]

On a personal level, we can adopt some of the strategies that promote unity (as well as our own well-being!) by treating others (ALL others!) with love and respect, even (or especially!) when it's difficult, and refuse to let powerful people manipulate our loyalty and passion for their own purposes. Research indicates that this approach actually prolongs our lives, and makes us healthier and happier! (Brooks, 2019)

To promote unity on a personal level, we have 3 tasks.

- One is to get to know and talk with people with whom we disagree - not with the goal of convincing them to agree with our beliefs, but to understand them, without judgment. This means avoiding ascribing motives to other people without taking the time to understand them. Braver Angels, a citizens' alliance that was created a few years ago to depolarize America, offers guidance and training for doing this in settings that are conducive to understanding each other.

- Another task is to avoid judging or characterizing other people or groups of people.

What people are DOING, or the POLICIES they are promoting, may be deplorable or stupid or thoughtless or harmful, but people themselves are way too complex to be labeled and put into a category. The only people who label others or ascribe motives to them are people who haven't bothered to get to know them. So try to catch yourself labeling or judging others, and vow to get to know them better.

This means also being on the alert to notice every instance of others judging or holding contempt for people, and call them on it or tune them out. When listening to political candidates and media personalities, I am interested only in those who refrain from labeling and categorizing others. As Brooks (2019) says, whenever someone gets us to hate, they are profiting -- we need to stop being used by the "outrage industrial complex, and politics and media" that is feeding the polarization and the "us vs. them" mentality and extremism which is threatening our way of life.

-

The last task is the hardest, but I've found it to be the most gratifying, helping me reduce my stress and deal with a world that can sometimes seem overwhelming.

It is to consciously love those whom we think are doing bad things, sincerely wishing them well while we fight and oppose or deal with what they are doing. Let's heed the family of one of the victims of the shooting in El Paso who urged us not to turn their tragedy into a reason to hate anyone.

In my own case, it was surprisingly easy for me to love the man who changed our lives forever when he ran over our son, and wish him peace and happiness as he serves out his prison term. I find it much harder to love the politicians whose policies seem to me to be incredibly harmful, polarizing or greedy, and even harder to wish them well. But once I accomplished that (managing to love them and wish them well), I was surprised at how much it reduced my stress, made me feel more at peace while I did everything in my power to oppose their policies or decisions.

One strategy that helps me love these "enemies" is explained by Jean-Robert Bayard (2018). The strategy is to think about what the "enemy" is doing that is so detestable, and then find an example where we ourselves have done something similar. For example, when I see our political leaders doing something that seems discriminatory or repressive, I work to remember times that I have dismissed or ascribed negative characteristics to a group of people. It makes me cringe with embarrassment but it helps me understand. And whenever someone says something hurtful or ignorant, I work to remember doing the same. The next part of this exercise is my favorite -- it is to forgive myself for these negative things and realize that I am still a good person, and then do the same with the "enemy." As Bayard explains, once we recognize these failings in ourselves and manage to understand it, we can understand and deal with it in others. [NOTE: Click here to see a workshop on using this strategy, "Take the perspective of The Big You while dealing with your opponents."]