You will find references to each of the above links as you read the suggestions below.

Recognize if there is a Situation of Uncertainty for gap judgment:

That is how I teach people to identify Situations of Uncertainty. First I teach them what a Situation of Uncertainty is -- for ideas about this, see "Introducing Situations of Uncertainty to Students." Once they understand this, I present them with a variety of situations, and ask them to identify which are Uncertain and which are not. I then verify whether they are correct in each situation by analyzing it with the TMAD. This strategy of presenting situations and verifying the student's judgment is called the Procedure to Develop Judgment of the Detection of Traffic.

However, it is nearly impossible to recognize Situations of Uncertainty or determine when it is clear to cross without an "internal/cognitive" understanding of crossing time (not just knowing how many seconds it takes to cross, but having a functional understanding). Therefore, before students can learn to recognize Situations of Uncertainty, they should know how to determine the width of the street they want to cross (this can be done without vision) and understand their crossing time .

Determine the width of the street you want to cross:

- Blind people can determine the probable width of unfamiliar streets by listening to the traffic.

Of course this requires a conceptual undertanding of lanes, as well as the ability to determine how far away are the lanes in which traffic is traveling.

Below are some strategies for teaching these concepts and skills.

- understanding what are "lanes" and how wide lanes typically are:

Once the students seem to understand the width of the lanes, have them walk across a street or an area with traffic lanes (if they can see the markings, have them close their eyes, or have them walk in an area that is not marked) and have them report when they think they have reached the end of each lane and are beginning the next. Practice until they can do so accurately.

Congenitally blind students can examine vehicles in parking lots to become familiar with the width of cars and trucks and understand the reason for the width of the lanes needed to accommodate them. However, be aware that the width of parking spaces is usually about 8 feet wide, which is more narrow than the width of lanes in the streets (about 10-14 feet wide).

- Explain that although there are many exceptions, most streets are symmetrical, so that if there are two lanes going one way, there are usually two lanes going the other way. However an extra lane is usually inserted at busy intersections for left-turning traffic entering the intersection, and there is sometimes a parking lane on one side of the street but not the other.

- Have the students face a street with multiple lanes of traffic going the same direction, and listen to the vehicles. As the vehicles pass, tell them which lanes those vehicles are in.

It usually doesn't take students long before they can independently identify the lanes themselves, just by listening (see Workshop for examples).

The ideal street for this training is a one-way street with more than 2 lanes, but two-way streets with more than two lanes going in one direction work well also. The reason you want the traffic all going in the same direction is because you don't want the student to be able to guess which lane a vehicle is in by the direction it is traveling -- the vehicles in all the lanes that you are using should be traveling the same way.

-

Have students stand at the edge of the street and listen to which lanes are used by the traffic coming from the left (the near side of the road) and which lanes are used by traffic from the right.

The students will then use knowledge of typical street geometry to calculate how many lanes wide the street is likely to be.

For example, if they can hear traffic from the left in the second lane, and in the third lane they hear traffic from the right, they know that there are only 2 lanes coming from the left. Since most streets are symmetrical, there are probably 4 lanes altogether.

Understand ("internally/cognitively" understand) how much time you will need to cross streets of various widths:

- Once the student knows how wide the street is and you have timed the student crossing it (or crossing the equivalent distance), ask the student to imagine crossing the street, beginning when you start a timer.

Based on the student's actual crossing times, report when the student would have completed the crossing (that is, when the time that the student needs to cross has passed).

It often helps if you report to the student when she would have reached the second lane, the third lane, the middle of the street, the last lane, etc.

- Next, ask the student to imagine crossing the street, reporting to you when she starts her imaginary crossing and when she thinks she would have reached the other side.

Start a stopwatch when the student reports that the imaginary crossing has begun, and stop the watch when the student predicts she would have reached the other side, then tell the student whether she was accurate.

The exercise continues until the student can accurately measure the time needed to cross. (See examples in Vignette #1 and in Workshop.

This may be reversed and the instructor asks the student to imagine starting to cross, then interrupts and ask the student to report where in the crossing she would be at that time. The ability to determine this will be helpful later, when the student is listening or looking for approaching vehicles -- the student can predict where in the crosswalk she would have been if she had started to cross just before detecting an approaching vehicle and the driver hadn't slowed down for her.

- NOTE: When students are learning to judge the time needed to cross, do not ask them to simply count the seconds, just as you would not ask them to count steps when they are learning to judge distances.

Although some students enjoy the challenge of accurately measuring the passage of time and seconds (and doing so can be a fun additional exercise for these students), it is more important that they develop an "internal" or cognitive understanding of the passing of time during their crossings.

Once the students have learned to determine the street's width and understand how much time they need to cross, use the Procedure to Develop Judgment of the Detection of Traffic to teach them to recognize Situations of Uncertainty. This procedure uses the Timing Method for Assessing the Detection of Vehicles (TMAD) in a variety of situations to help students learn to observe and recognize situations where they cannot hear or see the traffic well enough to know whether it is clear to cross.

See "Introducing Situations of Uncertainty to Students" for ideas about starting to teach your student to recognize Situations of Uncertainty.

The Self-Study Guide recommends that you read the following:

Use hearing to determine when it is clear enough to cross, and recognize the masking effect of ambient sounds:

- It is surprising how many students who must rely on auditory information to cross streets are unaware that sounds such as receding vehicles or other traffic movements (such as traffic at a nearby intersection or roundabout) can reduce their ability to hear approaching vehicles.

Just listening to approaching traffic to notice how far it can be heard in various acoustic conditions is usually sufficient for students to learn this, especially if the sounds are compared objectively by measuring the time from when each approaching vehicle was heard until it arrives at the crosswalk.

For example, when it's quiet, as soon as you hear a vehicle from a distance, listen as it approaches. If there is a second vehicle behind it, or if there is a car approaching from the other direction, notice that the second vehicle isn't audible until it gets much closer than the first vehicle was when you heard it -- sometimes the second vehicle is not even heard until after the first vehicle passes. Many students have no idea why the second car wasn't heard until it was so close, and must be told it was because the sound of first vehicle masked it.

Another effective strategy is to have the student compare the detection of approaching vehicles when it's quiet with the detection when there is a steady background noise at various volumes. Use the Timing Method for Assessing the Detection of Vehicles (TMAD) to help the student objectively measure the detection of approaching vehicles when quiet, and then use the TMAD to compare that to the student's detection of approaching vehicles while a steady noise is present. The steady noise can be provided with a recording of white noise or a recording of a vacuum cleaner or steady traffic noise.

The degree by which increasing ambient sound can affect the ability to hear the approaching cars can vary in different situations, and students should be able to recognize whether they can still hear the traffic well enough if it becomes a little noisier (click here for more information).

Use vision effectively to determine when it is clear to cross, and do it when glancing left-right.

- Students who have functional vision need to

understand the effects of various lighting conditions, sight lines, and features of vehicles on their ability to see them.

For example, they can notice the effect of bends in the road, hills and objects which block their view of the traffic,

notice what features of the vehicles make them easy/difficult to see (color, headlights, sun reflection, approaching directly vs. at an angle, etc.).

Compare the detection of approaching vehicles under ideal lighting conditions with the detection when the lighting conditions are not good.

Most importantly, these students need to be able to determine when it is more efficient to use hearing than vision, and vice versa (for example, see both lessons in vignette #4).

Once students have learned to determine if it is clear to cross by watching steadily in one direction, they should learn to make that same determination by looking to the right and left. This means they need to glance or scan from left to right and back -- see "Scanning for Cars" for more information.

"Scanning for Cars" is recommended by the Self-Study Guide.

Judge when the vehicles are far enough and/or slow enough to allow you enough time to cross, and do it when glancing left-right.

- The Timing Method for Assessing the Speed and Distance of Vehicle is an effective tool to teach students to make that judgement, and can be adapted to teach them to do it when glancing.

"Timing Method for Assessing the Speed and Distance of Vehicles" is recommended by the Self-Study Guide.

Analyze risks and decide if they are acceptable.

- Once people realize they are in a situation where they cannot be certain whether it is clear to cross, they need to consider how risky it would be to cross there, so they can decide whether to accept the risk or look for alternatives.

A Vignette gives an example of these kinds of issues, and the following are some of the considerations of which students should be aware.

- pedestrian and white cane laws regarding right-of-way.

-

Many people have misconceptions about who has the right of way and what pedestrians must do to gain the right of way; what effect the white cane or dog guide has on a pedestrian's right of way and what are the "white cane laws"; whether it is legal for pedestrians to cross midblock; etc. Orientation and mobility specialists should be thoroughly familiar with and teach their students the laws in their state or province as well as generalities about similar laws in other states and provinces (Sauerburger, 1999).

- probability that a vehicle that was undetected at the beginning of the crossing could reach them before the crossing is finished.

-

In situations where the student cannot be sure that it's clear to cross, there is a wide range of probabilities that when the student starts the crossing, there is an undetected vehicle approaching which would have to slow down or stop to avoid hitting the student.

When students find themselves in situations where they cannot be sure whether it's clear to cross, have them consider (compared to other such situations) how likely it is that, when they start their crossing, there is an undetected vehicle that is approaching and would have to slow down or stop to avoid hitting them. For example, they should understand that the probability of that happening is greater at busy streets than at streets where there is seldom any traffic, and it is greater at streets where the traffic is very fast and cannot be heard until it's very close than it is where the traffic is slower and can be heard further away. They also need to know that the probability will vary depending on the time and the day of the week.

Students who are deaf-blind may need to learn to get assistance from someone with vision or hearing to analyze situations and assess the probability that a vehicle might approach during their crossing at various times of day. They can have the assistant indicate the movement of the vehicles, for example by pointing to them as they pass by, indicating the speed and volume of the traffic (see suggestions). This can give the deaf-blind person an understanding of the typical traffic situation at that time of day, so that he can determine how likely it is that as he starts to cross, an undetected vehicle will approach which will have to slow down or stop to avoid hitting him. - likelihood that drivers will slow down or stop to avoid hitting the student.

-

Teach the student about the drivers' need for sight distance, braking time, and good road conditions.

The student should realize that drivers may need several seconds to react and start to brake when they see something in their path, and additional time is required to bring the vehicle to a stop.

Statistics of the distance required to stop at various speeds are available from the Federal Highway Administration, and can help students understand that drivers need to be able to see the pedestrian far enough away to be able to stop.

- Fitzpatrick, Turner, Brewer, Carlson, Ullman, Trout, Park, Whitacre, Lalani, and Lord (2006);

- Geruschat and Hassan (2005) who studied the percentage of drivers at various speeds who stop for pedestrians with a white cane crossing at Maryland roundabouts;

- Inman, Davis and Sauerburger (2005), who studied drivers at a roundabout, and

- Sauerburger (2003), who studied the percentage of drivers who yielded to a person with a white cane trying to cross separate right-turn lanes in California and in Maryland.

-

Finally, have the student observe the yielding behavior of drivers in the student's area.

This information may be more applicable to the student's situation than the results of studies in other areas.

Have the student try to get drivers to yield in various situations and observe (with sighted assistance if necessary) how many drivers comply.

Students also need to understand that drivers are less likely to take the necessary action to slow down or stop in time to avoid hitting pedestrians who are not crossing where drivers are expecting them to cross, even if they have white canes, and in most states, pedestrians with white canes who are not in crosswalks do not have the right of way (Sauerburger, 1999). In addition, students need to understand that drivers are unable to control their vehicles and slow down or come to quick stops in some road conditions, such as during icy conditions or during light rains on roads that have been dry for a long time.

The student should also learn information from studies of the yielding behavior of drivers. Several studies have been done in the last few years to document whether drivers yield to pedestrians with white canes or dog guides. Among them are - danger of "multiple threats"

-

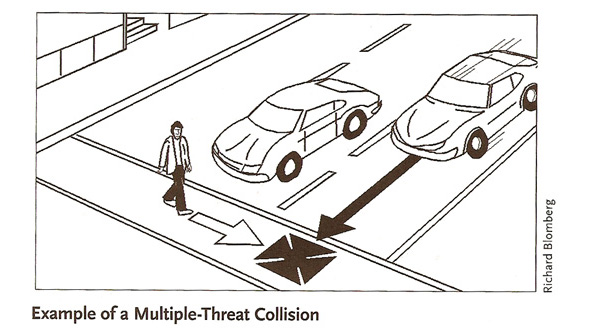

Most importantly, students should understand the dangers of crossing multiple lanes when there is a vehicle that has stopped to yield in only one lane, as shown in the illustration to the right (Barlow, Bentzen, Sauerburger & Franck, page 383).

This is how Dick and Lorraine Evensen were killed.

In this situation, the presence of a vehicle waiting in one lane can reduce the visibility of the pedestrian to other drivers, and reduce the ability of the pedestrian to hear other approaching traffic. Hopefully through training as described above, the student is already aware of the effect of sounds being masked or blocked by other vehicles, and is aware that there may be vehicles approaching in other lanes.

Students should also understand that they can not trust the verbal assurance of drivers or others that it is safe to cross.

Use alternatives if the risks are not acceptable or if less risky options would be preferable.

-

Pedestrians should always be able to opt out of crossings that they feel are too risky -- see the list of Alternatives When Crossing is Too Risky.

Below is a list of suggested activities for students:

- Have the student execute spontaneously-planned alternatives. For example have the student approach an intersection, evaluate the crossing and, if it's not possible to hear or see the vehicles well enough, consider the feasibility of various alternatives and implement one of those that doesn't require planning ahead (such as getting assistance, crossing elsewhere, etc.).

- Have the student listen or watch at a crossing where there is no traffic control, and determine whether it is likely that there is a traffic signal along that street in either direction and if so, how far away it is likely to be.

[Hint: Traffic signals cluster vehicles together into what traffic engineers call "platoons," and the further the traffic gets from the signal, the more spread-out are the vehicles.

So if the traffic comes in tight clusters of traffic followed by long gaps in traffic, there is probably a signal at the next intersection "upstream" in that direction, and if the groups of vehicles that are somewhat spread out, they may be coming from a signal a few blocks away.]

- Give the student assignments to go to destinations in familiar areas which have intersections where the student knows he cannot hear or see the vehicles well enough, and have him plan the route to avoid those intersections.

- Have the student contact traffic engineers responsible for troublesome intersections to consider the feasibility of revising the intersection to make it safer to cross -- click here for some ideas. To find out more about modifications and features that increase accessibility and safety for people who are blind or visually impaired, you might contact the Orientation and Mobility Division's Environmental Access Committee and the representative for your area in the U.S. and Canada.

References:

Barlow, J.M., Bentzen, B.L., Sauerburger, D. & Franck, L. (2010) "Teaching Travel at Complex Intersections," chapter in Wiener, W.R., Welsh, R.L., & Blasch, B.B. Foundations of Orientation and Mobility, Third Edition, Vol. II: Instructional Strategies and Practical Applications. AFB Press, New York, NY

Fitzpatrick, K., Turner, S., Brewer, M., Carlson, P., Ullman, B., Trout, N., Park, E., Whitacre, J., Lalani, N., & Lord, D. (2006) TCRP Report 112/NCHRP Report 562 - Improving pedestrian safety at unsignalized crossings. Transit Cooperative Research Program and National Cooperative Highway Research Program, Washington, D.C.: Transportation Research Board.

Geruschat, D. and Hassan, S. (2005) "Driver Behavior in Yielding to Sighted and Blind Pedestrians at Roundabouts" Journal of Visual Impairment and Blindness, AFB Press, Vol. 99, No. 5, p. 286-302

Inman, V.W., Davis, G.W., and Sauerburger, D. (2005) Pedestrian Access to Roundabouts: Assessment of Motorist Yielding to Visually Impaired Pedestrians and Potential Treatments to Improve Access. Federal Highway Administration Report DTFH61-02-C-00064

Sauerburger, D (1999). "Rules of the Road" September 1999 Newsletter, Metropolitan Washington Orientation and Mobility Association (WOMA)

Sauerburger, D (2003). "Do Drivers Stop at Unsignalized Intersections for Pedestrians Who are Blind?" Proceedings, conference of Institute of Transportation Engineers, March 25, 2003, Ft. Lauderdale, FL

Self-Study Guide: what next?

If you got this far by following the recommendations of the Self-Study Guide, you're almost ready for some fun reading!

Before you go on, however, be sure that you've read the following, each of which has already been recommended in your readings:

- (page 3) Procedure to Develop Judgment of the Detection of Traffic

- (page 4) Timing Method for Assessing the Detection of Vehicles (TMAD)

- (page 5) Timing Method for Assessing the Speed and Distance of Vehicles (TMASD)

- (page 6) Scanning for Cars

- (page 7) Street-Crossings: Analyzing Risks, Developing Strategies, and Making Decisions

This is the last page of serious stuff before you're ready for the fun pages, but you might find that this page is the most helpful of all -- it may provide you with an interesting, new perspective to help deal with complex street-crossing issues. I hope it is as helpful to you as it was for me -- enjoy!

Move next to page 7: Street-Crossings: Analyzing Risks, Developing Strategies, and Making Decisions

Return to Situations of Uncertainty for Gap Judgment

Return to Self-Study Guide - Preparing Visually Impaired Students to Assess and Cross Streets with No Traffic Control

Return to Home page