RE:view - Fall 2005

Teaching Deaf-Blind People

to Communicate and

Interact With the Public

Critical Issues for Travelers Who Are Deaf-Blind

Eugene Bourquin and Dona Sauerburger

Travelers with dual sensory losses present the rehabilitation professional with additional

tasks and responsibilities that expand the instructional curriculum. Effective

instruction in rehabilitation and orientation and mobility includes teaching strategies

and tools for dealing with unfamiliar people through communication (conveying information)

and interaction (knowing when and how to use specific communication techniques).

Incorporated in those two skills are acknowledging the public’s typical lack of

awareness of the nature of deaf-blindness, understanding that the traveler knows his or

her own needs better than others do, and being able to assert one’s needs effectively.

Teaching effective techniques for communication and interaction, skills that are critical

elements for the quality of everyday life, is a necessary component of comprehensive

rehabilitation. Unless instructors address these additional needs of students who

are deaf-blind (see note), comprehensive rehabilitation is not possible.

Although travelers who are deaf-blind present challenges because dual sensory loss

may affect many interpersonal transactions, professionals can and should design

instruction that addresses real-world circumstances and assist travelers in overcoming

barriers found in everyday activities. The past several decades have seen the development

of various approaches to addressing many of these challenges (DeFiore & Silver,

1988; Florence & LaGrow, 1989; Franklin & Bourquin, 2000; Gervasoni, 1996; Lolli

& Sauerburger, 1997; Sauerburger, 1993; Sauerburger & Jones, 1997). In this article,

we assume knowledge of these strategies and methods and will not present a detailed

review of those approaches. Rather, we consider the communication and interaction of

people who are deaf-blind with the public and the teaching techniques that we have

found effective. The techniques we present are the results of our collective experiences

with people who are deaf-blind, including several decades of instructing these travelers

in community-based and residential settings.

Effective Communication Strategies

Basic Considerations

Choosing which communication strategy to use depends on the person's hearing,

vision, and language skills; cognitive abilities; comfort; and assessment of the risk. The

more methods that the person can use skillfully, the easier communication with the public

will be. People who are deaf-blind can communicate with the public through gestures,

in writing (prepared or ad hoc), orally (spoken or prerecorded), or by presenting symbols

and pictures. The public can respond to the person who is deaf-blind by tapping the person

on the arm or shoulder, some form of written messages (e.g., printing on the palm of

the hand, using devices such as an alphabet card, writing on paper), speaking, presenting

yes or no signals, and exhibiting actions or behaviors.

Generic cards and tools are not always effective. The design of the communication

should match the physical and cognitive needs and skills of the person who is deaf-blind

and provide the public with quick and easy ways to respond. For example, cards may be

made that assist a person who is deaf-blind to arrive at certain destinations; that guide him

or her to the counter at a store or business, to a certain bus, across a street; or that provide

certain assistance on a train or airplane. The variety of cards and messages that can be

created is as endless as the list of specific needs of these travelers. Some situations require

a communication tool that provides the public with a limited choice of responses: for the

person who is deaf-blind and has limited understanding of English or to communicate

with people who have limited time, such as bus drivers or salespeople.

Communication cards can be developed for multiple purposes. A card may have a

variety of labels that can be attached with Velcro to complete a sentence, such as

"Please guide me to the (insert the name of a store or business)" or "I would like to

order (insert a food item)." In Seattle, people who are visually impaired can flag buses

by using tools in which the number of the bus is inserted into a clear plastic sleeve.

Examples of Tools Created for Specific Purposes

Examples of Tools Created for Specific Purposes

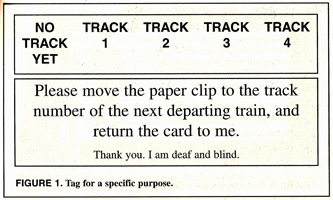

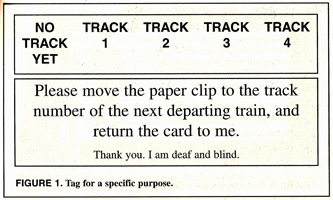

Scenario A. A man needs to ask a busy station clerk from which train platform his

daily commuter train departs. A communication card is designed that he could pass

through the glass partition to the clerk. The card has a series of track numbers along

the top in both print and Braille and a paper clip attached to the card at a default section

labeled "NO TRACK YET," to indicate that the clerk does not yet know from which

track the train will depart. A message on the card requests the clerk to move a paper

clip to the correct track number and return the card to the traveler. See Figure 1.

Scenario B. A woman who is hard of hearing and visually impaired wants to ask a

bus driver to let her off at the bus stop nearest to her destination but needs to find out

where that stop is. She makes a map of the appropriate area and writes a note asking

the driver to point to the bus stop nearest to her destination.

Scenario C. A young man who is deaf and visually impaired and has limited English

skills presents a salesperson with a note asking for a certain item. He is unable to understand

the salesperson's lengthy written response, which explains that the item is out of

stock and will be available when the truck arrives the following week. By creating a

fill-in-the-blank note (see Figure 2), he can indicate what he wishes to purchase and the

salesperson can let him know whether the store carries the item and if it is in stock or

when it will be in stock.

FIGURE 2. Example of a fill-in-the-blanks card.

I would like to purchase a _____________. Please check the following:

____ We have the item and I will bring it to you.

____ We do not carry that item.

____ We carry that item but it is out of stock; we should have it by ________.

Keep the Communication Simple and Focused

- Group related communication tasks and tools together. Travelers using public transportation,

for example, can use a plastic document holder or pencil case to store cards

or equipment to communicate with the bus driver, a fare card or change to pay for the

fare, identification and reduced fare cards, and other necessities such as emergency

information. A notebook, small photograph album, or a ring can hold separate sets of

communication cards developed for specific travel needs: one set for grocery shopping,

another for requesting items in a restaurant, and a third for traveling a route on foot.

- Cards should be easy to identify. Tactile indicators, such as corners that are cut or

bent or a Braille label, or visual indicators, such as color-coding the cards or having

pictures or symbols on the cards, such as a picture of a telephone, can help the person

who is deaf-blind quickly find the appropriate card. Each tool should be easy to use,

sequenced in priority or in the order in which it is to be used, and easily accessible physically.

Tools should also be comfortable to handle and store.

- The message should be short and concise. A message that presents a vague request

or an open-ended question may produce a lengthy and confusing response. For example,

text such as "I am lost. Can you help me? I am deaf and blind. Thank you" invites

a variety of responses. A narrow and pointed message such as the following will elicit

either a positive response or no response: "I am lost. Please call (name and phone number)

and tell them my current location. Tap my arm twice if you can help. I am deaf

and blind. Thank you."

The inability of the uninitiated public to identify quickly and easily the specific

assistance being requested can be a major impediment to effective communication

(Sauerburger & Jones, 1997). Many pedestrians and retail employees do not have the

time or impetus to comprehend a wordy request. Conveying messages or requests to

the public in simplified language typically provides the best results.

Effective Strategies for Interaction With the Public

In addition to knowing how to communicate with the uninitiated public, people

who are deaf-blind need to know how to interact with them: how to get someone’s

attention; how to assert their needs. Probably the most common problem that occurs

when interacting with the public is for the person who is deaf-blind to assume that the

other person knows they are deaf-blind and knows how to help and communicate with

them. When other people do not act as expected, the person who is deaf-blind often

assumes it is because those people are rude or do not like people who are deaf-blind.

They do not realize that the people have no ability to interpret this typical situation

properly. People who are deaf-blind sometimes begin to mistrust the public and avoid

traveling when and where they must interact with other people. Understanding the

following principles for successful interaction can help people who are deaf-blind

interact effectively:

1. The deaf-blind traveler should be aware that others do not understand the situation

and do not know what to do. Even when given an explanation, many people will

not understand because they are dumbfounded, are not paying attention, or are incredulous

that a person who is deaf-blind can travel independently. Therefore, the deaf-

blind person will need to explain, often more than once.

2. When asking for assistance, whether with a written or spoken message, it is best

to give the following information in this specific order: (a) the help needed (e.g., crossing

the street, finding the correct bus, getting information), (b) exactly what the person

who is deaf-blind wants the other person to do, (c) an explanation that the person is

deaf and blind or visually impaired and hard of hearing, and (optional) how to communicate

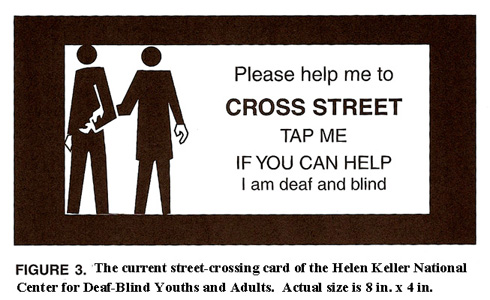

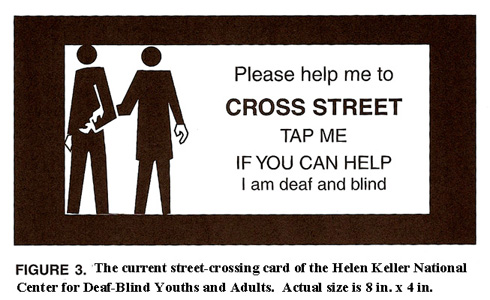

(Sauerburger & Jones, 1997). See Figure 3.

Getting the Public's Attention

To communicate effectively with the public, people who are deaf-blind need to get

people's attention and convey that they want to communicate or receive assistance. To

do this, it is best for them to stand where they are most visible and where others are

likely to be, at locations such as a bus stop or store entrance. More people are likely to

be at street corners than at midblock. People who are deaf-blind should make certain

not to stand behind a bush or pole where they cannot be seen. They can use an electronic

travel aid to recognize when people are passing, go into stores or businesses to

find people to help, or perhaps even approach people's homes, if they are not concerned

about the safety of doing this.

Having gotten people's attention, travelers who are deaf-blind must make it clear

that they want assistance, or the public will simply pass by (Sauerburger & Jones,

1997). The following strategies may be effective for this purpose:

- Use body language. Effect a puzzled look; shift the body as if uncertain or looking

for help. Do not stand confidently and smile.

- Hold up a card or speak or use a tape-recorded message that asks for specific help.

Large, brightly colored cards with big, bold print attract more attention. Recorded messages

must be clear and sufficiently loud to be understandable. In many environments,

it is impossible to hear recorded messages.

Building Backup and Fail-Safe Tools

A fail-safe strategy is one that reliably informs the user when techniques are not

working; a backup plan handles situations when the original strategy does not work or

unpredictable situations occur. Developing several ways to communicate and interact

increases the probability of a successful interaction.

A fail-safe strategy and backup for a commonly occurring problem. Travelers who are

deaf-blind use communication cards to inform bus drivers where they want to get off the

bus. Frequently, drivers misunderstand and assume that the communication card is something

else, such as a bus pass, or they simply refuse to read the card (Cioffi, 1996).

One successful strategy is to have a card that requests the bus driver to keep the card

until the bus arrives at the desired location and then return it as a signal that it is time

for the traveler who is deaf-blind to get off. The traveler presents the driver with the

front of a communication card on the bottom of which are the words "PLEASE KEEP

THIS CARD UNTIL WE REACH MAIN STREET AND FIRST AVENUE." The bus

driver glances at the card without reading it and signals the rider to proceed into the

bus. The traveler again presents the card for the driver to read and keep. The driver,

still not reading or understanding the card, does not take it. This card is a fail-safe

strategy because the traveler automatically knows it is failing and can implement the

backup plan.

The traveler then turns over the card, where a message in large print reads "PLEASE

READ THE OTHER SIDE OF THIS CARD. I AM DEAF AND BLIND. THANK

YOU." When presented with this message, the driver reads the message on the front

and keeps the card. If the driver does not, the traveler leaves the bus.

For longer trips on public transportation on which the person who is deaf-blind is

relying on the driver or conductor to inform her when to get off, the traveler may be

forgotten and miss her or his stop because public transportation employees attend to

many tasks and deal with many customers. Therefore, devising a way to reconnect

with the employees and remind them of the traveler's destination is often wise. The

person who is deaf-blind can set a timer at the beginning of the trip to alert him or her

when it is time to remind the employee that the destination stop or station is coming

up soon. (Vibrating kitchen timers are readily available in many catalogs of independent

living aids.)

Devising backup procedures for the various situations that may arise puts decision

making into the hands of the individual who is deaf-blind. Incorporating them into travel

plans may circumvent frustrating and unsuccessful experiences and give the traveler confidence

and security.

Conclusion

We believe that this area of inquiry is rich with potential and mostly unexplored.

Insufficient published research exists concerning the many communication and interaction

possibilities for travelers who are deaf-blind. Many of those individuals navigate

simple and complex communication situations daily, and probably many of their strategies

and successes are as yet undocumented.

We have found that the following procedure has proven highly effective for communicating

and interacting with the public.

Preparing for Experiences With the Public

- The instructor and traveler consider possible communication techniques and

choose as many as are appropriate and feasible.

- The traveler practices the techniques and becomes skillful with them. The instructor

reviews with the traveler the two principles for successful interaction listed on page 113.

Before Going out on Each Session

- The traveler prepares all necessary notes, cards, or equipment.

- The traveler prepares backup plans or fail-safe procedures.

- The instructor and traveler brainstorm ways that the traveler can get people's

attention and assistance in each expected situation.

Trying the Communication Techniques With the Public

It is best if the traveler first practices simple situations that eventually become more

unstructured. An example of the hierarchical order to follow for lessons starts with

getting help to cross streets (very structured communication). The next steps are shopping

in small stores, shopping in large department stores, riding a bus, and, finally,

soliciting aid to reach an unfamiliar destination or when lost.

The instructor does not prepare the public for the interaction ahead of time. During

the interaction, the instructor observes unobtrusively and does not intervene. Thus, the

person who is deaf-blind can experience actual interaction and learn the effectiveness

of her or his communication skills. After the experience, the instructor provides objective

feedback about what he or she observed, brainstorms with the student about why

the interaction did or did not work, and suggests new ideas to improve the interaction.

Instructors should be aware that the level of acceptable risk and benefits of communication

and interaction with the public must be decided only by the person who is

deaf-blind. Although the instructor can teach strategies and explain possible consequences,

individuals who are deaf-blind must judge each situation for themselves and

make the final determination of whether to incorporate or reject techniques. What

might be a simple task for one individual may be untenable for another person. As part

of instruction, rehabilitation professionals should include self-assertiveness and self-

advocacy as a primary component to the greatest degree possible.

NOTE

We have chosen to use the term deaf-blind. This is the nomenclature of the major consumer

organization in the United States, American Association of the Deaf-Blind (AADB), and the

largest rehabilitation agency, the Helen Keller National Center for Deaf-Blind Youths and Adults.

It was also the preference of individuals who are deaf-blind in a survey conducted by AADB.

REFERENCES

Cioffi, J. (1996). Orientation and mobility and the usher syndrome client. Journal of Vocational

Rehabilitation, 6, 175-183.

DeFiore, E. N., & Silver, R. (1988). A redesigned assistance card for the deaf-blind traveler.

Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 82, 175-177.

Florence, I. J., & LaGrow, S. J. (1989). The use of a recorded message for gaining assistance with

street crossings for deaf-blind travelers. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 83,

471-472.

Franklin, P., & Bourquin, E. (2000). Picture this: A pilot study for improving street crossings for

deaf-blind travelers. RE:view, 31, 173-179.

Gervasoni, E. (1996). Strategies and techniques used by a person who is totally deaf and blind

to obtain assistance in crossing streets. RE:view, 28, 53-58.

Lolli, D., & Sauerburger, D. (1997). Learners with visual and hearing impairments. In B. B.

Blasch, W. R. Wiener, & R. L. Welsh (Eds.), Foundations of orientation and mobility (2nd ed.,

pp. 513–529). New York: AFB Press.

Sauerburger, D. (1993). Independence without sight or sound: Suggestions for the practitioner

working with deaf-blind adults. New York: AFB Press.

Sauerburger, D., & Jones, S. (1997). Corner to corner: How can deaf-blind people solicit aid

effectively? RE:view, 29, 34-44.

Return to O&M for Deaf-Blind People

Return to Home page

Examples of Tools Created for Specific Purposes

Examples of Tools Created for Specific Purposes